If one single factor has determined the course of Seychelles colourful history, then it is the fact that, as a country, it was settled relatively recently, in the mid-18th century, by French colonists and their retainers or, as the story goes, by a prophetic assortment of ‘15 whites, five Malabar Indians, seven Africans and a negress’.

So much for settlement, but the unrecorded history of the islands that appear on a number of the earliest maps, predates this by many centuries and has also coloured the character of the islands and their evolution into the nation state that we know today as Seychelles.

In around 600 BC a Phoenician expedition sent down the Red Sea by pharaoh Necho II of Egypt circumnavigated Africa and returned through the Pillars of Hercules after three years. Did they make landfall in the islands we now know as Seychelles? We have to be content with conjecture with regards to this fascinating prospect.

In around 600 BC a Phoenician expedition sent down the Red Sea by pharaoh Necho II of Egypt circumnavigated Africa and returned through the Pillars of Hercules after three years. Did they make landfall in the islands we now know as Seychelles? We have to be content with conjecture with regards to this fascinating prospect.

The first people to pass by the islands and probably use them as temporary shelters were the ancestors of the people who eventually populated the nearby island of Madagascar. They rode the oceans on primitive but rugged outrigger canoes from their home in the Sunda Islands of the Malay Archipelago sometime between 200 and 500 AD and it is likely some of their craft, blown off course during their spectacular migration, used the islands as a base before venturing on into the azure vastness to what would eventually become their new home.

Early Arab explorers came across these island jewels dotted in a lost corner of the western Indian Ocean as they made their first forays into what they called ‘bahr al zanj’, (the sea of the blacks) which was perhaps a reference to the spoils of early expeditions when they captured slaves from the east coast of the African continent.

It is clear from certain early manuscripts of Perso-Arab origin that the Arab mariners of as early as the 9th century knew these islands as jazayer é zarrin (the golden isles) which is how their unreal natural beauty must have appeared after months sailing on a featureless ocean. The atoll of Aldabra, one of Seychelles farthest outposts, carries an Arabic name which means ‘the green one’: another reference to an island popping up, literally, from out of the blue. Certain rough island graves have also been attributed to Arab sailors who never made it home from their long, hazardous expeditions into the great watery unknown.

Portuguese navigator Juan de Nova made the first recorded landfall in the Seychelles in 1501 followed by a sighting of her Amirantes group by the celebrated Vasco de Gama in the following year. On early Portuguese maps, Seychelles appeared as the Sete Irmas or Seven Sisters but would have to wait until 1609 for the first landing of a squadron from the English East India Company whose crew brought back tales of the islands’ abundance, the koker nuts and the fierce ‘allagartes’ that patrolled the surrounding waters.

The next group of people to visit Seychelles and use it as a lair were the pirates. A little known historical fact places a large pirate community on the island of Ile Ste. Marie off north-western Madagascar in the early 1700’s as they fled, first the Caribbean and then the Cape Verde Islands to find a haven in the unknown waters of the western Indian Ocean. In Ile Ste Marie they founded their own pirate republic – Libertalia, complete with its own laws and language and they managed a commercial operation so large that it even tempted the Americans to travel for the first time into the Indian Ocean. Some of the great pirates of the day: Irving, Teatch, White and Kidd made an appearance at some point in Libertalia. It is even claimed that, from there, around 1720, Olivier Levasseur, known as La Buse, travelled to Seychelles with three ships where he concealed a fabulous booty he raided from the Vierge du Cap among the hills of Bel Ombre in northern Mahé. To this day, the treasure has never been found, even though it is claimed artefacts from this horde have made their way into certain private collections.

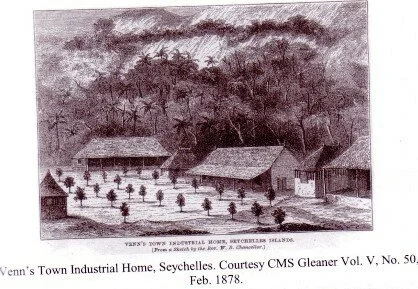

The pirates came and went but, after several exploratory expeditions, the French finally claimed the islands’ beauty as their own, first occupying Ste Anne island before moving on to Mahé.

The first few years of the colony were hard times. The harvests failed, the settlers faced starvation and their commanders lost control. The grandly named Jardin du Roi spice garden project ended in fiasco. In May 1780 a ship was sighted from Mahé. Believing it to be English and not wanting the garden to fall into enemy hands the gardens were burnt to the ground. When the ship sailed closer it was discovered to be French after all. But by then it was too late: the gardens and the spices, save a cinnamon tree or two, were completely destroyed. Other man-made destructions occurred in those early years: the tortoise population on Mahé was decimated with many hundreds of tortoises shipped to Isle de France or eaten by the settlers. By 1778 they were almost completely wiped out on Mahé. The endemic Seychelles crocodile was also hunted to extinction as were several species of birds.

The year 1789 saw the start of the French Revolution. The colony in Seychelles at this time consisted of 69 French, including three soldiers, 32 free ‘coloureds’ and 487 slaves. In 1790 the French community, fired by the new spirit of revolution, set up their own Assembly and Committee, announcing independence from the Isle de France. But the newly independent colony did not last long. One by one the great declarations of independence were dropped, particularly the abolition of slavery, which was not at all popular with the colonists. Eventually it was agreed that the powers of the committee should be given to a new commandant who would be able to govern more effectively. The new commandant was a popular choice: Captain Queau de Quinssy (later spelled Quincy).

He was not only the longest serving Governor of the colony, but also achieved the most during the long troubled years of the Napoleonic Wars. During these wars the islands changed hands between the French and the English several times, and it was Quincy who repeatedly capitulated (no less than seven times!) to avoid bloodshed. It was soon agreed that Seychelles should be a neutral port to the English and the French and so the settlers avoided the conflicts and blockades that other Indian Ocean ports suffered. This also suited the many French corsairs who were sailing the Indian Ocean plundering enemy ships: Mahé became a popular port of call for many of the most notorious corsairs of the day.

The British fought for Seychelles and Isle de France because both island nations were strategic points on the route between India and the Cape, and because the corsairs remained a menace. In 1810, after a long blockade, Isle de France capitulated and the British renamed it Mauritius. That Seychelles would become British property was now guaranteed, and duly occurred in 1814. Quincy remained in office under British rule and died on Mahé in 1827 at the age of 79. He was buried with full honours near Government House, where his impressive grave still stands today.

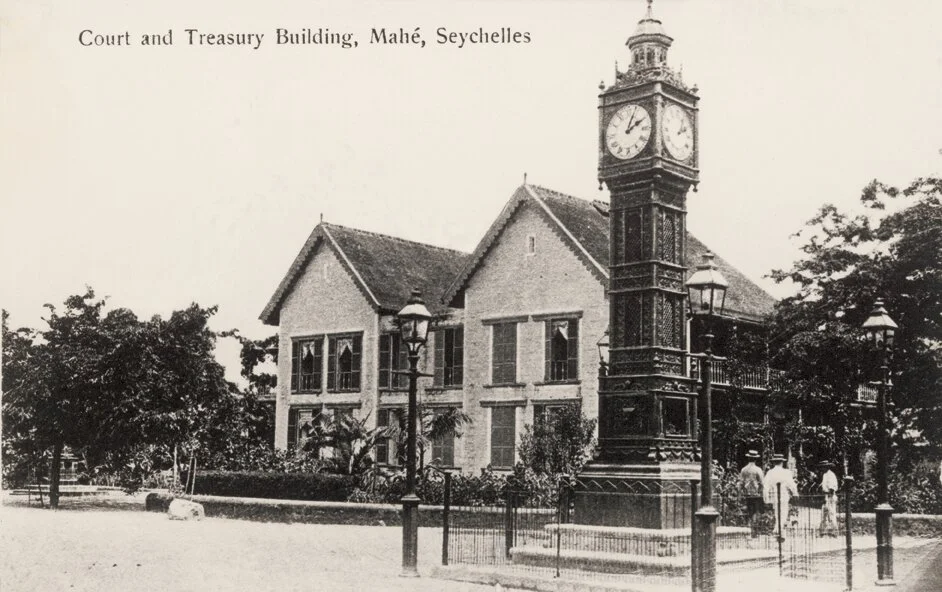

During the British colonial period, Seychelles gained roads, schools, churches and a hospital. By 1900 the population had grown to 7,000 and in 1903 Seychelles became a crown colony in its own right, separate at last from Mauritius. The British Governor commemorated the event by erecting a clock tower in the centre of Victoria, a replica of the clock tower at London’s Vauxhall Bridge.

Although a British colony, the culture of Seychelles remained steadfastly French. British Governors did attempt to anglicise the islands, but with little success: customs and language did not alter much during the British colonial era.

It was during the Second World War that the winds of political change began to stir in Seychelles and, shortly afterwards, universal adult suffrage was granted. In 1962 two political parties were formed under the leadership of two lawyers who were to remain the main political figureheads for the rest of the century: France Albert Rene and James Mancham. Independence from Britain was gained in 1976, and today Seychelles is a Republic (population 93,000) within the British Commonwealth under the leadership of President Danny Rollen Faure.

Thanks for sharing. It does refresh my memories. I learn Geography at school, some of it, completely forget. Thanks again for refreshing my memories.

You’re most welcome. Glad you liked the article.

Wonderful to see this brief history of a country I have come to love – although only having visited a few times.

Is there a book covering the history of these wonderful islands and does anyone know if Madam Rene ever published her planned book of her childhood on Curiese Island?

Stay beautiful Seychelles – you really are a jewel in the ocean.

Hi David.. Unfortunately, it seems Madam Rene never published the book.

As for books covering the history of Seychelles, below are a few suggestions of books which are available locally:

At last, soonmee comes up with the “right” answer!

Finding this post has anrsewed my prayers

Englehtining the world, one helpful article at a time.